Like many people who live on this disaster-prone coastline, he knew what would eventually follow – a wall of water. Letter from Moscow: When war suddenly explodes over your roof Yet even in this country, with its culture of stoicism in the face of adversity and emphasis on the collective, the people of the Tohoku region stand out for their resilience amid such a wrenching moment. Most of the destruction has been repaired, the more than 200,000 people who lost homes have largely been resettled, and work is progressing on the long decommissioning process at the badly damaged nuclear plant. Minamisanriku, in that sense, mirrors the rest of Japan a decade later. But much of the activity of daily life has returned. Empty lots and open spaces dot parts of the landscape, in between the soba noodle restaurant, offices, park, and shopping center that have been rebuilt as the town was moved to higher ground.

Haga now dedicates his time to giving talks on what happened that day and how the town is working to revive itself.Īfter the unthinkable human loss and almost total physical destruction, some wondered whether Minamisanriku would continue to exist as a town at all. They had power beyond human imagination,” says Chouko Haga, who has spent all of his 72 years in Minamisanriku, 47 of them working for the local fishing cooperative. “This town was buried by waves in five minutes.

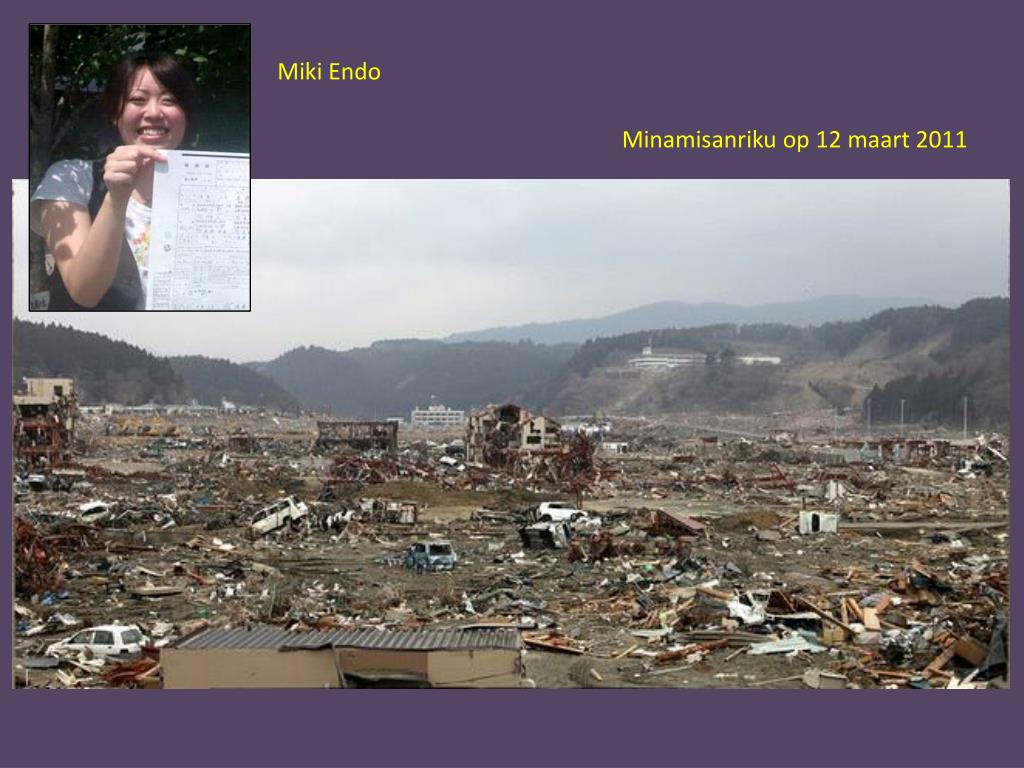

Few places were hit as hard as Minamisanriku. A magnitude 9.0 earthquake triggered waves that inundated more than 200 miles of coastline, killing 18,500 people and setting off a nuclear disaster at the Fukushima nuclear plant that reverberated around the world. Ten years ago the town was struck by the most powerful tsunami in Japanese history. Minamisanriku hums with a quiet rhythm, which in itself is perhaps remarkable. Minamisanriku has become a symbol of resolve as it resurrects itself after the 2011 tsunami. Many fishing villages along Japan’s northern coast have an intimate and fraught relationship with the sea. Some of those who work the cobalt waters run bed-and-breakfasts to supplement their income, though fishing has always been the lifeblood of the town. This striking tableau helped make Minamisanriku a popular tourist destination. Similar terrain continues inland through the hills that surround the town on three sides. The craggy inlet that leads into this fishing port is banked by steep slopes blanketed with trees. Saito goes shrimping every day – and has the weathered face and calloused hands to prove it – making his living from the briny waters as generations before him have done in Minamisanriku. Tomoaki Saito is carrying crates from his 20-foot shrimp boat to a small, white truck parked on the quay. It is a Saturday afternoon and many of the people who work the sea have finished for the day, but a few still tend to boats and nets. Still, the temperature is low enough to chill even the hardy fishermen and women who toil on the water off this mountainous stretch of Japan’s northeast coast. A snowstorm warning has been issued but there is no sign of flakes in the slate gray sky. She says with a laugh: “It was really crazy that I spent five years of my life doing this!”īlisteringly cold gusts blow in off the ocean and sweep across the boat landing.

#Miki endo your name full#

“America is an amazing land full of storytellers,” she says.She’s also aware that some people would find her compulsive need to map novels slightly, well, obsessive.

Straight is also a collector of stories as she travels, including the ones she hears from gas station attendants, truckers, and truck stop servers. “If you want to know how somebody in Alabama feels, read one of the books set in Alabama,” she says. Ms. Straight says her literary map rejects red-state/blue-state divisions in favor of human empathy and understanding. That was super fun.” She calls her project 1,001 Novels: A Library of America. Beyond the map’s cool factor, the featured novels offer insights into the people of a particular place. “Here’s the 7-Eleven or here’s the campground in Alaska. If she wasn’t certain, she contacted the authors. “I tried to find exact locations for everything,” she says. Instead, using Google Maps, she pinpointed the places where each of the novels was set. And she didn’t simply plunk a marker down in the middle of a state and call it good. Straight, a professor of creative writing at the University of California, Riverside, started a project – just for fun – to create a literary map of the United States. As she passes through regions of the country on one of her epic road trips, she views people and landscapes through the lens of literature. Growing up, “Books were this huge deal to me, and books were how I learned about America,” she says in a video interview. When Susan Straight travels, she sees novels. When Americans travel, they see mountains and valleys and oceans.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)